Fossilisation, ‘the long term persistence of plateaus of non-target-like structures in the interlanguage of nonnative speakers’ (Selinker and Lakshmanan, 1992, p.197) refers to the idea that a learner’s interlanguage system reaches a point where the development of some or all of their interlanguage forms ceases, without having reached a native-like state.

As I said in my talk, it was the combination of my students’ stubborn errors and the many examples of my own stalled development that led to fossilisation becoming a bit of an obsession of mine.

Han says that despite ‘abundant exposure to input, adequate motivation to learn, and plentiful opportunity for communicative practice’ (2013, p.137) acquisition stops before the learner reaches target language mastery’.

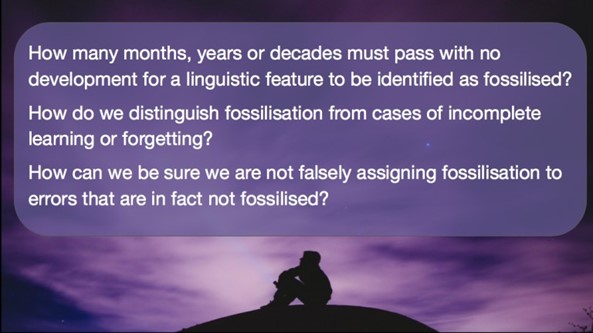

It seems reassuring on one hand to think ‘Hey, it’s not my fault that I keep making these errors – it’s fossilisation!’ But I think it’s also problematic. Fossilisation implies the end state when no further progress in that particular area can occur. The idea of just accepting that something has reached the end state raises all these questions…

Han (2013) says that some teachers embrace the concept, but falsely assign fossilisation to errors that are in fact not fossilised, while other teachers refuse to believe that it exists, as this would imply a situation where no learning is happening. Understanding fossilisation would ‘lead to efforts to maximise learning while entertaining realistic expectations about the learning outcome, whereas ignorance would lead to use of non-differentiated strategies, which diminishes rather than enhances learning’ (Han, 2011, p.480)

After all my research into the topic, I have decided to side with the scholars who suggest that a more neutral term such as ‘stabilisation’ should be used (Mitchell et al., 2013), as it does not imply a permanent cessation of development, but I’ll be keeping Han’s comment about differentiated strategies in mind.

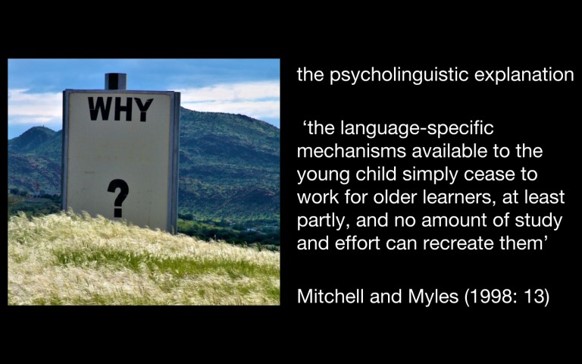

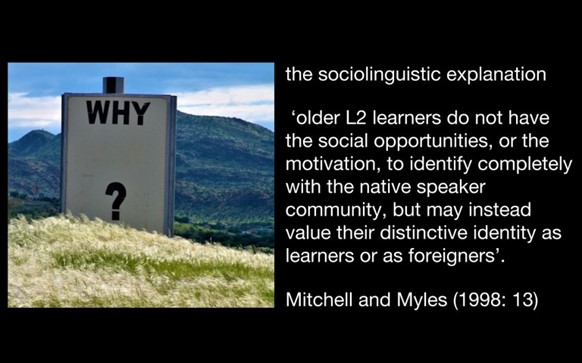

First off, I looked at why progress stalls, be it permanently (fossilisation) or temporarily (stabilisation).

In other words, the causes are age, attitude, motivation and acculturation.

This idea of learners resisting the process of acculturation, becoming part of the native speaker community, struck a chord with me. I had never really considered that learners might prefer to retain their ‘other’ identity, as learner or foreigner, which is ironic because … Lightbulb moment … that is exactly what I’d been doing. Being an English speaker is a huge part of my identity. It has enabled me to work in different countries, it influences my social life (my closest friends are all English-speakers from around the globe) and my home life (raising a bilingual child). I realise now that it’s a possible barrier to progression. I want to be fluent, but at the same time retain my ‘other-ness’. No wonder I didn’t care about eliminating certain errors in grammar or pronunciation.

Now I’ve figured out that to take action against fossilisation, we all need to get busy reflecting.

‘Reflection enables us to correct distortions in our beliefs and errors in problem-solving’ Mezirow, 1990

I discovered quickly that you can’t just tell people to reflect. Reflection is very personal, not everyone is open to the idea immediately, and many ask ’What am I supposed to do? How do I reflect?’ You need to give guidance.

There are a lot of resources online to help get you started. I found edutopia.org‘s 40 Reflection Questions a good place to start. https://www.edutopia.org/discussion/scaffolding-student-reflections-sample-questions

Introducing reflection takes time, regardless of the questions or prompts you decide to use. You can’t assume students will know what you want, or be comfortable with it, but you can build up to it, and make it part of every lesson. You could add a question for the class on what tasks they enjoyed most, or get them in pairs to talk about the things they found hard during the lesson. As time goes on, and they get used to it, set more difficult questions, about their own learning and their feelings towards their progress. We often gauge our own performance by comparing ourselves to others so not everyone might be comfortable talking about this in front of class. But the main goal is to get us thinking about our learning, and what works for us, what doesn’t and why that could be.

You could also encourage your students to keep a learning notebook. There are also journalling apps or websites.

Personally, I prefer paper and coloured pens, but having the digital record is very convenient too.

What I use for German evolved from a vocab notebook into something more like a messy diary, a place for random thoughts, questions about language, things I heard in passing, goals, things that frustrate me. I find it useful to be able to look back and reflect on previous reflections. I write in English. Anything else seems too much like homework and for me the focus is reflecting on my learning, not the reflecting being the learning.

As a result, I think students should be able to choose which language they write in, and whether it is something they keep private or share with you. It will completely depend on who your students are, of course. If they write in English, you can offer to correct it for them, every now and again.

Once students are reflecting on the tasks they enjoy, their progress, where they are having difficulties, the next step is working out how to increase their success.

‘Some language learners seem better than others at learning languages and the better ones sometimes do different things than poorer language learners’ Gass and Selinker, 2008

Strategies, the steps learners take to process, store and acquire the knowledge they are presented with, appear to be the key to success at learning. How successful a particular strategy is will depend on the learner and the situation, but helping learners identify which strategies work best for them gives them a sense of autonomy, which helps maintain motivation.

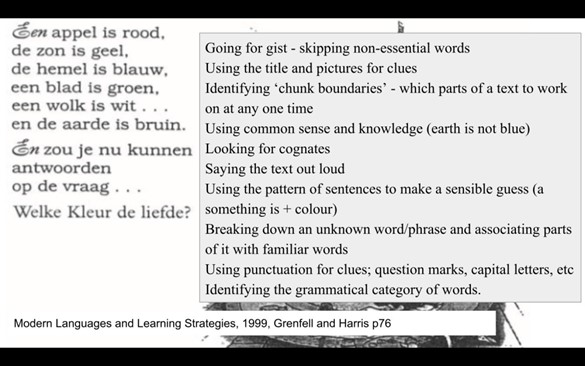

Despite all my interest in the idea of strategy training, I procrastinated for ages, reading a lot on the topic but not really doing anything about it in class, until I came across the book Modern Languages and Learning Strategies (1999, Grenfell and Harris) and the task where students collaboratively translate a Dutch poem. I used it in my talk as I think it is ideal for demonstrating the benefits of strategy training, and also how easy it can be.

A task like this asks you to consider all the different things you can do when faced with a challenge in language learning. It reminds us that with a second language, it is not of simple matter of knowing the meaning or not – we can use all kinds of tools and tricks (i.e. strategies) to experiment with understanding.

There is a lot of information on learning strategies online:

- Helping learners learn:exploring strategy instruction in language classrooms across Europe, Vee Harris http:// ecml.at/documents/pub222harrise.pdf

- Language Learning Strategies: Theory and Research, Carol Griffiths http://crie.org.nz/research-papers/ pdf

Sometimes learning is not transparent for students. People often say, ‘I had English at school but I never learned much – my teacher wasn’t very good.’ They see their success or lack of success as being the responsibility of the teacher. Of course, having a connection to the teacher helps, but the teacher just guides the way, the student has to do the learning. Reflection and strategy training makes this more manageable and success more achievable.

I hope I’ve motivated you to give reflection and strategy training a go. Let me know how you get on!

‘A major goal of formal education should be to equip students with the intellectual tools, self-beliefs, and self-regulatory capabilities to educate themselves throughout their lifetime’ Bandura, 1993

References:

Gass, S.M. and Selinker, L., 2008. Second Language Acquisition: An Introductory Course. Routledge.

Grenfell, M. and Harris, V., 1999. Modern languages and learning strategies: In theory and practice.

Han, Z., 2013. Forty years later: Updating the fossilization hypothesis. Language Teaching, 46(2), pp.133-171.

Lee, E., 2009. Issues in fossilization and stabilization. Linguistic Research, 26(2), pp.151-166.

Mezirow, J., 1990. How critical reflection triggers transformative learning. Fostering critical reflection in adulthood, 1, pp.20.

Mitchell, R., Myles, F. and Marsden, E., 2013. Second language learning theories. Routledge.

Selinker, L. and Lakshmanan, U. 1992. Language transfer and fossilization: The multiple effects principle.

Language transfer in language learning, pp.197-216.

Laura Edwards teaches Business English to university students, and also work in test development and teacher training. Over the last few years, she has moved into the field of online learning by developing concepts and content for digital tests and online materials for students at all levels of the Common European Framework. In 2017 she completed her MA in Technology, Education and Learning. Her focus is on language learning, communication, creativity and technology.

Laura Edwards teaches Business English to university students, and also work in test development and teacher training. Over the last few years, she has moved into the field of online learning by developing concepts and content for digital tests and online materials for students at all levels of the Common European Framework. In 2017 she completed her MA in Technology, Education and Learning. Her focus is on language learning, communication, creativity and technology.

No Comments Yet